Historically Black Neighborhood Faces New Challenges

Zoning change sought to preserve Elm Thicket/Northpark character

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the first story in a series looking at the conflict between neighbors in the historically Black Elm Thicket/Northpark community.

Diane Johnson’s dad worked two jobs to pay for the family home her 109-year-old mother still lives in. From that home, the family has watched the Elm Thicket/Northpark community for decades.

“A lot of people who lived over in this area — I know my dad, Mr. Masters, Mr. Young — all these people worked at the airport,” she said. “They were mechanics, they worked on airplanes. They did that all their lives until they retired. And it took them working two jobs sometimes to pay for these houses.”

The Elm Thicket/NorthPark neighborhood is bordered by Inwood, Lovers, Bluffview, Lemmon, and Mockingbird. Within those confines, a historic freedman’s town grew up, sheltered first among a thicket of elm trees that gave the community its name.

Now, the historically Black neighborhood looks a lot different. The homes families bought intending to pass on as generational wealth — sometimes generational wealth gained for the first time — are dwarfed as two and three-story structures rise up as quickly as the more modest abodes they replaced are demolished.

And it’s pitting neighbors against each other as some fight to preserve the character and history through a proposed zoning change, while others think the change stands in the way of progress.

The zoning changes, which were recommended by the Elm Thicket Authorized Hearing Steering Committee would limit height on new construction, as well as enact lot-size coverage restrictions for new two-story homes, and restrict the types of roofs used in new construction.

Existing records indicate that the freedman’s town of Elm Thicket (named after the thicket of elms present on the land) was settled by at least 1912, but possibly earlier. Newspaper articles from the 1920s describe “small-but-modest” houses in a thriving community. It was also home to a resort, a baseball field, and the largest barbecue restaurant in Dallas at the time — Eltee O. Dave’s BBQ.

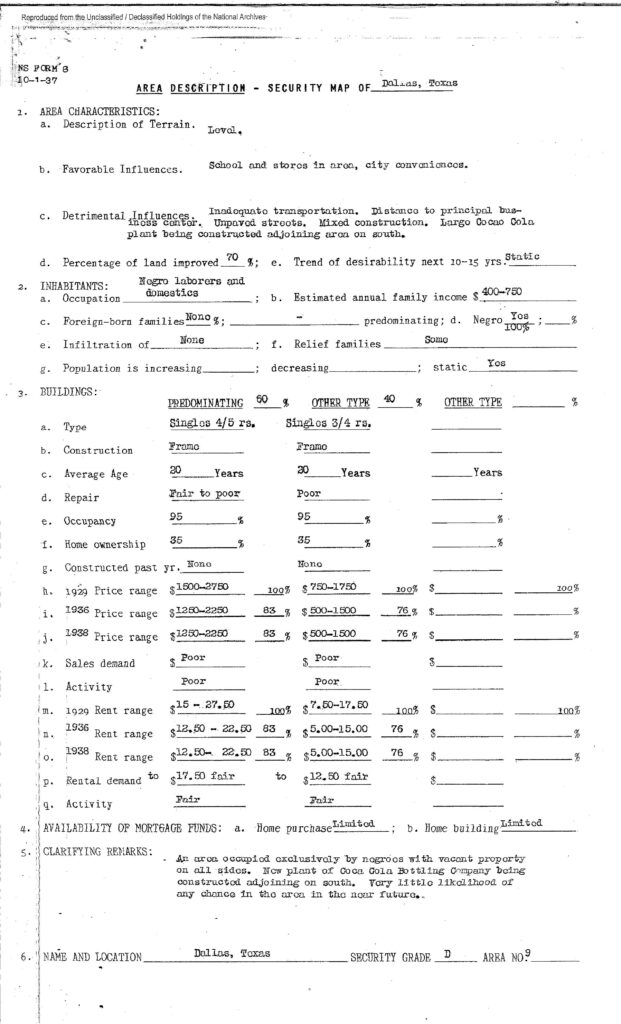

As time marched on, many Black neighborhoods were also subject to redlining, a practice that came into favor in the 1930s as federally-backed mortgages began to be offered.

Before the Great Depression, the standard 80/20 30-year mortgage was not the standard at all. Homeownership tended to be for the wealthy, or those who could afford high down payments and short lending terms, renegotiating a mortgage every year.

But in an effort to jumpstart the economy and create jobs, the federal government stepped in and created the Home Owners Refinancing Act of 1933, which created the Home Owner’s Loan Corp., or HOLC. Mortgages became available, and color-coded maps were drawn to explain the risks for loaning in certain areas.

The Home Owners Refinancing Act of 1933 created the Home Owner’s Loan Corp., or HOLC. Color-coded maps were drawn to explain the risks for loaning in certain areas.

Green was the most desirable areas — buyers would be able to qualify for a loan of up to 80% (Highland Park, for instance, was always green). Blue was slightly less desirable, with the promise of only 60-80%. The least desirable was covered in angry red lines — and buyers in those areas would not qualify for any federal home loans.

Green areas were exclusively White and Protestant. Blue areas were mostly White, but also could have a mix of other ethnic origins like Jews, Italians, and Irish. Redlined areas were almost exclusively Black.

Those lending restrictions also made it difficult to fund new business, too.

“Area occupied almost exclusively by negroes with vacant property on all sides,” the HOLC description for the redlined section of Elm Thicket read, also noting that it had inadequate transportation and unpaved streets.

The practice would continue officially until 1968.

Postwar expansion ate away at Elm Thicket. The expansion of Love Field and relocation of Lemmon Avenue between 1953 and 1955 took hundreds of Black homes, as well as land that had been earmarked for Elm Thicket Park for Negroes and a golf course for Black Dallas residents, Hilliard Memorial Golf Park. Businesses that employed the residents of Elm Thicket began to close to make way for the expansion, too.

The residents facing displacement fought — and even sued — the city, but ultimately lost their fight against progress.

Follow along here as we explain the fight between neighbors bubbling over in Elm Thicket/Northpark.

Thank you so much for writing this article, our parents moved here when we were in the second grade in 1965 and as we got older my mom would have us write out $80 money order every month back then this was a lot of money, Mom was a domestic worker (maid) cleaning white people homes I’m sure making little of nothing working so hard and then coming home to a husband and nine children who needed her attention, dad work long shifts so we could afford to stay in our home which we loved, you see our parents wanted more for there children. This is a good neighborhood a close knit community and family oriented, some say that this is not an historic neighborhood but if you check and talk to some of the older neighbors who are still alive and family member who are living here today they will share stories how there parents all wanted something better. We love living in this community and have no desire to move anywhere else. It’s really sad that people can come in an decide to take what’s not there’s this has been happening for years and it needs to stop, destroying neighbors and causing dissension and discord among the people. Thank you for taking the time to write this article and for reading my thoughts.

Georgia Clark

My neighborhood I think I’ll Keep it

Thank you for bringing attention to this wonderful neighborhood that I grew up in. I feel frustrated as I see the changes happening in Northpark which I know effect the long standing residents in a negative way. I grew up on Kaywood Drive with my great grandmother Elsie Morris, my mother and brother. I am currently in the process of finishing art works about this neighborhood and the effects of gentrification which will be on view at 500X Gallery from August 27th – September 17th.

I invite you to attend the reception which will be held Saturday, August 27th from 7-10pm at

500X Gallery

516 Fabrication St.

Dallas, TX 75212

– Jamila Mendez