Absent Widespread Testing, Texas Schools Are Limited on Coronavirus Prevention

Republished with permission.

By Emma Platoff

The Texas Tribune

Ideally, students and teachers returning to classrooms this fall would be tested for the novel coronavirus “as much as in major league sports,” says Diana Cervantes, an epidemiologist at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. In Texas, that will not happen.

With no plans for widespread testing and a virus still spreading quickly in many communities, “schools should be prepared to have infected individuals show up,” said Spencer Fox, a University of Texas at Austin researcher who models coronavirus risks.

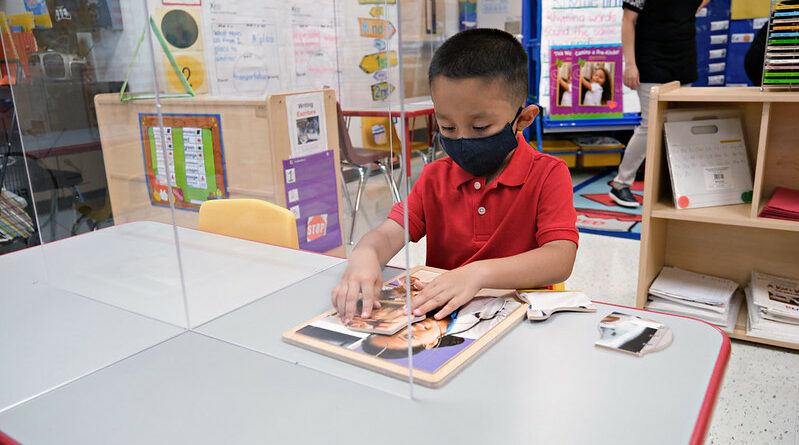

Infections are inevitable in schools, and administrators will face the challenge of keeping them from growing into outbreaks that force school shutdowns and spark community hot spots. Employing many mitigation measures, experts say, is the best strategy: mask-wearing, hand-washing, keeping students in isolated cohorts, ensuring proper ventilation and holding class outside whenever possible.

The many Texas schools preparing for in-person classes next week will be largely on their own to devise precautions against a virus that spreads silently in as many as 40% of those it infects. Guidance from the state education agency is heavy on recommendations, light on requirements. In many districts, there will be soap and hand sanitizer aplenty, social distancing and physical barriers where possible, and no required testing.

Many experts believe that community spread will be the inevitable result.

“The reality is, unless you’re doing routine testing, you’re not going to be able to identify those kiddos who are asymptomatic and presymptomatic,” Cervantes said. “Schools have to come in with the assumption that there will be positive children walking around their hallways every day. … They feel fine, they look fine, but they are spreading the virus.”

Balanced against health concerns are the educational needs of the more than 5 million public school students in Texas. Experts say students learn best in schools, and in-person classes are especially important for students with disabilities. In many parts of the state, students learning remotely will receive a worse education, some struggling just to get online. And for many children, being in school means food, medical care and a refuge from abuse.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has said districts “should start with a goal of having students physically present in school,” but also acknowledged that “the current widespread circulation of the virus will not permit in-person learning to be safely accomplished in many jurisdictions.”

Cases are still growing in Texas, and the share of coronavirus tests that turn up positive is around 10% — a figure Gov. Greg Abbott called a “warning flag,” and far higher than the 5% benchmark some experts say communities should be below before reopening schools.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does not recommend universal testing in schools, and bare-bones guidance from the Texas Education Agency does not encourage testing asymptomatic staff members or students as a prevention strategy. That’s in part because large-scale testing in the U.S. generally, and in Texas in particular, is still not feasible.

Over the last week, Texas performed an average of about 45,000 viral tests per day. The Houston Independent School District alone has well over 200,000 students.

Still, some large districts across the nation are making an attempt. The Los Angeles Unified School District plans to test 700,000 students and 75,000 staff members. And Detroit public schools plan to require negative COVID-19 tests for all in-person staffers, with the hope that there will be enough testing capacity for all students.

Many of Texas’ biggest districts — Houston ISD, Dallas ISD, Austin ISD and El Paso ISD among them — will not require testing of anyone at any point. Individuals who know or suspect they have COVID-19 will be instructed to stay at home through the 14-day incubation period, according to state guidelines. But they can return to campus without being tested if they show improvement over a specified period of time.

“Very few [districts] will probably have access to testing. But we know some things about the epidemiology of the disease. Even if you don’t have a lot of testing, at a minimum, if you distance the kids and if everybody over 2, including the teachers, wears masks, and people don’t come back to school sick, you should be able to control the number of infections in your school,” said Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, a Stanford pediatrics and infectious disease expert who is advising Los Angeles schools on testing. “I’m not saying you’re going to have zero, but you can probably control the number.”

Each individual prevention measure is somewhat effective, but “altogether they can be very effective,” Cervantes said. “Layer on all of those things.”

Some Texas districts that are open for in-person classes have already reported coronavirus cases, and experts expect those numbers will grow as more children return to classrooms.

Dumas ISD, a Panhandle community hit hard by the coronavirus this spring because many in Moore County work at a meatpacking plant, has already seen coronavirus cases since it opened weeks ago, but the numbers have been manageable, Superintendent Monty Hysinger said.

With football starting, “I think those numbers will elevate slightly,” Hysinger said.

“I’m hoping we kind of find our balance point there, and we can just maintain that,” he said. “Right now it doesn’t look like it’s going to be out of line.”

The district is taking safety precautions — mandating frequent hand-washing and sanitizing, hiring additional janitorial staff. But some of the best practices that scientists recommend are simply not feasible.

“We can’t promise, and we haven’t promised, our parents that we can socially distance,” Hysinger said. “We just don’t have the space, and I don’t know of a district in the state that has the space.”

Dumas, like many districts across Texas, is asking parents to screen their kids before they come to school each morning. The TEA says schools must require staff to self-screen for coronavirus-like symptoms, and parents must not send children to school if they suspect they may be sick. But screening is likely to miss asymptomatic cases — as are common mitigation strategies like temperature checks.

San Elizario ISD, near El Paso, has spent about $64,000 on 24 temperature-scanning kiosks placed at the employee and student entrances of each campus. It also spent $5,000 on no-contact thermometers for bus drivers to screen students before they get on buses.

But the TEA does not recommend school districts regularly check otherwise asymptomatic students for fevers, since many students with COVID-19 do not have any symptoms.

Financial constraints will also limit districts’ efforts. The governor has promised to reimburse a portion of expenses related to COVID-19, but many districts are concerned that won’t fill the holes in their budgets.

Outside Texarkana, in Maud ISD, where classes have already begun, administrators delayed construction projects so they could afford to hire more janitorial staff and add a bus route. The district could not afford high-tech temperature gauges, so teachers have had to start checking kids’ temperatures at the door.

“Anything we felt was nonessential we stopped last spring” to save money, said Superintendent Chris Bradshaw. “We don’t have lots of money sitting there waiting for us to find a way to spend it.”

Research shows that children are less likely to suffer severe symptoms of COVID-19 than are adults. But kids with preexisting conditions like asthma or diabetes may be especially vulnerable. And children — even when they are not showing symptoms — can transmit the virus. Early research shows older kids may be more likely to transmit the virus than younger children, but scientists are still studying the question.

In some ways, it’s “a big experiment,” given how little is known about children’s vulnerability to and role in spreading the virus, said Catherine Troisi, infectious disease epidemiologist at UTHealth School of Public Health in Houston.

State health and education officials will provide weekly updates on how many cases school districts report among their staff and students. But it will be difficult to draw conclusions from that data alone about how risky reopening has proved, because there will be limited information about who is catching the virus in which schools. And it’s unclear whether the state will report how many districts are open in person or how many students are attending schools in person, so it may be impossible to say what share of students attending Texas schools have gotten sick there. Districts will also be required to report to the state whether cases were contracted on or off campus — a question that will be difficult to answer without robust testing and contact tracing efforts.

Some school districts, including Longview ISD in East Texas and Premont ISD in South Texas, are exploring plans to test students and staff.

But in many places it is out of reach financially, is impractical given limited resources or feels politically impossible.

“I think my folks would have a heart attack if I was like, ‘We’re doing random testing tomorrow,’” said John O’Brien, superintendent of Van Vleck ISD, a district of about 1,000 students in Matagorda County near the Gulf Coast. “Being in a very rural community, a conservative community, I have a lot of folks that think this is all baloney. This is like the flu. And I don’t believe that, and to be honest, none of my folks at school do.”

O’Brien said he believes the district has gone above and beyond — requiring people to self-scan before entering the building, putting UV light into the heating and air-conditioning systems to purify the air, spending $9,000 on three thermal cameras to alert when people with high temperatures are walking down the halls — but that testing would be a no-go unless the state required it.

“If we have a kid get sick, we tell mom, we can’t make them go get tested, but we can say, ‘Hey, we highly recommend you do,’” he said.

Aliyya Swaby contributed reporting.

The Texas Tribune is a nonpartisan, nonprofit media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them – about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.