The Family Place: Four Decades of Service

Kager Howard swore she would never be a victim of domestic violence. Josie Horn watched her father abuse her mother. And Hope Woodson left an abusive marriage only to see her son lash out in anger.

Theirs are just a few of the stories from people The Family Place has helped the past 40 years.

Back in 1978, when Gerry Beer and other activists opened the state’s first shelter for battered woman and children, such stories were mostly unwelcomed.

“There was a strong force that said, ‘You’re breaking up marriages,” Gail Griswold, the shelter’s first executive director, said of the resistance faced from clergy, law enforcement, and others.

Griswold was just two years out of Northeastern University, where she earned her master’s degree in counseling psychology when she joined The Family Place.

“We were so young and idealistic,” she said, looking at a photo of herself and others who challenged the system by advocating for services and laws protecting those impacted by domestic violence.

The memory took her back to a meeting with former Dallas police chief Billy Prince about plans for a larger shelter. “He was so dismissive of us,” Griswold said. “He told us we could open a shelter as big as a hotel, but it would be useless.

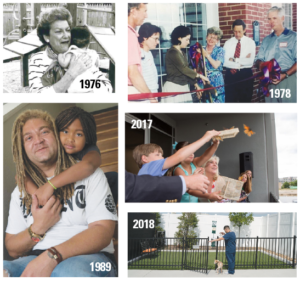

((1976) Gerry Beer establishes the Battered Women’s Task Force to address the need for social services for abused women and children in Dallas. Over the years, that initiative led to the opening of The Family Place (1978); Sally’s House (2000), the state’s first shelter for battered men (2016); the Ann Moody Place (2017), which also gave guests an opportunity to house their four-legged friends. Photo courtesy: The Family Place)

“But this seemed so fundamentally important,” she said. “There were no doubts.”

Paige Flink, who has been involved with The Family Place since the 1970s and serves as its CEO, explained how the nonprofit was mostly unknown then and addressing a topic people saw as just a private family matter.

If they didn’t experience it, they didn’t care, she said.

Flink remembers going to the little shelter in Oak Cliff during her years as a journalist at D Magazine and being dismayed by a woman holding a baby while digging through a garbage bag of clothing behind the barred windows.

“It just struck me that here is this person and this innocent child who’s hiding from someone who’s supposed to love them,” she said.

Images like that and a belief that they could make a difference despite people saying they couldn’t – or shouldn’t – inspired pioneering women to do something about an issue they found unacceptable, Flink said.

The Family Place became a national model with the opening of its children’s therapeutic program. It launched specialized counseling for batterers, opened housing, and helped change laws and educate first responders.

The nonprofit created programs to educate students about bullying, teen dating violence, and sexual assault. It expanded services, added beds and transitional apartments, and in 2016 opened the first men’s shelter in the state.

But there is still a long way to go.

“After more than two decades at The Family Place, I can tell you that victims (still) fear they won’t be believed, because their abusers said no one would listen,” Flink said. “It’s time to turn our attention to the abusers, to tell batters, “We see you,” and get them the help they need.”