St. Mark’s Graduate Strives to Right Wrongs

Work of Robert Edsel’s Dallas foundation spans countries, decades

By: Karen Chaney

While studying art and architecture in Florence in 1996, Robert Edsel began asking questions about World War II.

One changed the course of his life: “How, during a world war, did so many of the great works of art and cultural treasures survive, and who were the people that saved them?”

The St. Mark’s School of Texas graduate who grew up in University Park spent the next decade pursuing answers.

“The United States set the gold standard for the protection of cultural treasures during conflict with no tools of technology and with a handful of men – and once the war was over, women,” he said. “In all, the Monuments Men and Women found and returned to the rightful owners more than 4 million stolen objects.”

Edsel located and interviewed 21 Monument Men and Women, from the United States and Great Britain, conversations that led to him creating a foundation, receiving the National Humanities Medal from then-President George W. Bush, and writing four books on the topic.

He also consulted George Clooney for the film, The Monuments Men (2014), based on Edsel’s second book, a No. 1 New York Times Bestseller.

In 2007, Edsel launched the Monuments Men Foundation, which, in 2020, became the Monuments Men and Women Foundation.

The Dallas nonprofit aims to raise awareness about and honor the service of Monuments Men and Women and continue their work of returning missing art and cultural objects to the rightful owners.

The foundation has returned 40 items from prized paintings to Adolf Hitler’s leather-bound photo albums containing images of art and furniture stolen by the Nazis.

“The bad guys wanted to prove to their leader what a good job they were doing looting Jews and other victims of the Nazis,” Edsel said.

Edsel described the personal impact of handling the albums, knowing “Hitler’s fingerprints are all over the outside of the cover and on every single page of these albums.”

“It’s a terrifying moment, a disgusting moment, euphoric moment, and it’s certainly a historic moment,” he said.

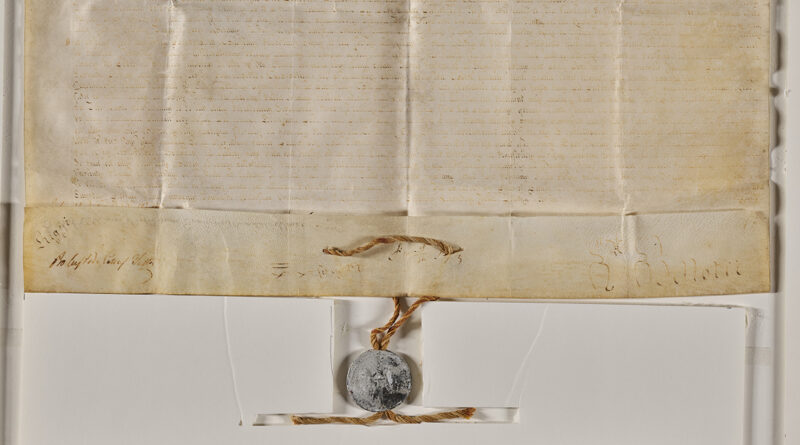

A recent restitution project involved a Papal Bull – a public decree issued by Pope Pius IX in 1862 to establish the Catholic Church of Santo Stefano in Scascoli, just south of Bologna in Italy.

“During WWII, in Italy, there was immense destruction to many of the nation’s churches and monuments,” Edsel added. “In the spring of 1945, when American forces passed through, there, an American officer happened to see this document among the rubble. Having no idea what it was, he picked it up and brought it back home as a souvenir of war. There it sat, in his home in Minneapolis, for decades.”

Eventually, Wolfgang Lehmann’s nephew contacted the foundation, and researchers determined its origins.

The foundation worked closely with the Kimbell Art Museum to enhance the faded, ancient Latin text and with Vatican scholars to understand it, Edsel said. “The expert at the Vatican read it easily, and as they had a copy of it, they knew what it was pretty quickly.”