Happenings on the Hill

Not the Loch Ness monster?

At a university known for its Mustangs (or Ponies), SMU researchers sure love their dinosaurs.

A recent CT scan has paleontologists talking about the minimal evolution in a long-extinct marine reptile with a striking resemblance to the mythical Loch Ness monster.

“Basically, in anything except living fossils, you don’t go 22 million years without evolving,” said Louis Jacobs, professor emeritus of Earth Sciences at SMU.

Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs were the largest of the long-necked plesiosaurs, growing as long as 43 feet with half of that length deriving from their small heads and very long necks.

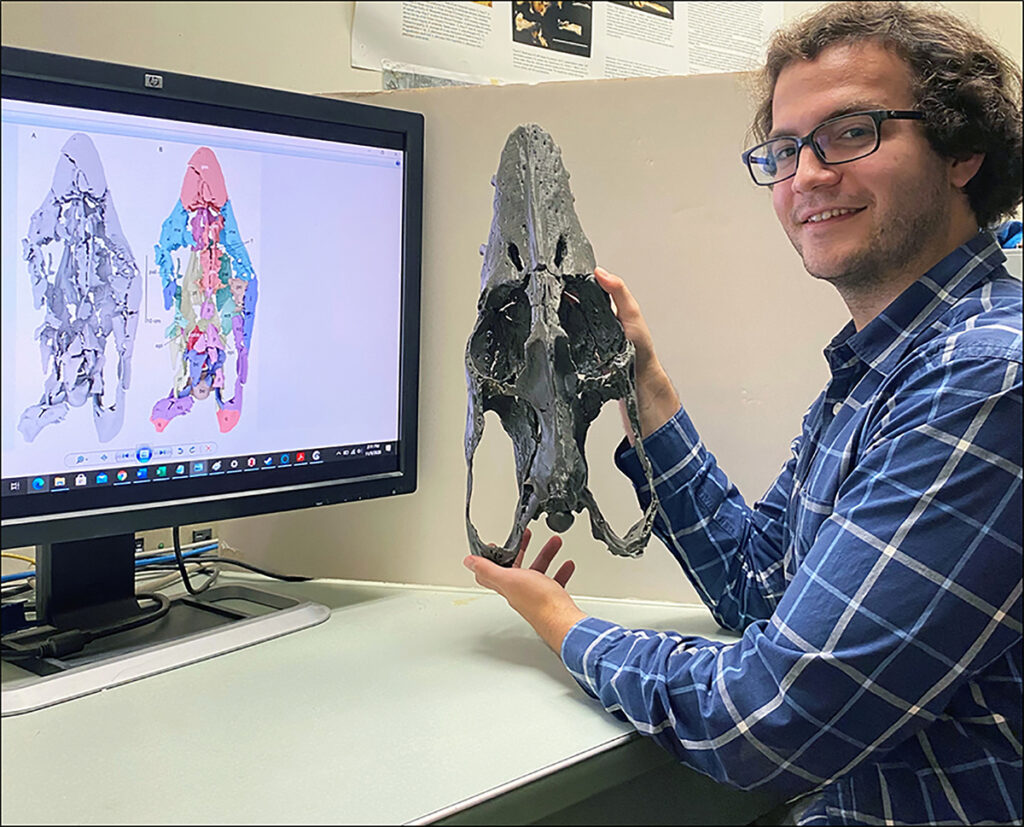

A CT scan of a 71.5-million-year-old skull from a species called Cardiocorax mukulu looked in 3D models nearly identical to those from much older elasmosaurids, including one found at Cedar Hill, Texas, in 1931. See its 93-million-year-old remains at SMU’s Shuler Museum of Paleontology.

“The skull shape, organization of muscles, and the shape and arrangement of the teeth largely reflect how an animal acquired prey,” said co-author Michael J. Polcyn, research associate and director of SMU’s Digital Earth Sciences Laboratory. “It appears that this animal’s predecessors adopted a particular feeding style early in their evolutionary history and then maintained the same basic skull structure for the next 22 million years.”

Of race and roadways

For SMU engineering graduate student Collin Yarbrough, a classroom assignment to evaluate the design of Dallas’ Central Expressway resulted in a recently published book about the long-forgotten history of Dallas’ racist past buried beneath the city’s freeways.

“I saw the same pattern of injustice over and over,” Yarbrough said. “From Tenth Street to Fair Park to Deep Ellum, the history of Dallas highways is part of a tangled web of infrastructure, policy, and race.”

Among his findings:

In the 1940s, frontage roads to Central Expressway paved over more than 1,000 graves of Black residents buried in Freedman’s Cemetery. Construction of Central Expressway bisected a thriving Black community.

The construction of I-35 in the mid-1950s led to the demolition of significant homes and businesses and split a thriving Black community founded initially by formerly enslaved people. The Tenth Street Freedman’s Town Historic District is on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s 11 Most Endangered Places.

In the 1960s, I-345, formerly part of Central Expressway, was redesigned to become elevated over part of the area known as Deep Ellum, limiting foot traffic and shuttering a once Black-owned commercial and residential district.

The Dallas native knew nothing about the racial history buried under the highways he traveled every day until he researched his paper, which led to his book, Paved a Way, Infrastructure, Policy and Racism in an American City (New Degree Press, 2021).

Writing a paper on Central Expressway changed his life, Yarbrough said. He began work in the fall on a doctorate in civil engineering at SMU, specializing in transportation, economic geography, and urban economics.

“Infrastructure is symptomatic of a larger ill – racism,” he said. “I’d like to seek ways to prevent infrastructure from promoting racism again.”