DMA Exhibit Explores Postwar Era Art

Featuring 91 works from the Dallas Museum of Art’s (DMA) collection of contemporary art and important loans from local private collections, Slip Zone: A New Look at Postwar Abstraction in the Americas and East Asia explores how artists revolutionized their forms, materials, and techniques in the decades following World War II.

The exhibition, which opens Sept. 14, reevaluates the art historical legacy of the postwar era to encompass simultaneous and intersecting international movements and trends, highlighting the crucial contributions of artists working in Buenos Aires, Mexico City, New York City, Osaka, Rio de Janeiro, Seoul, Tokyo, and beyond

In these artistic centers, abstraction afforded possibilities for new methods of art making, sometimes incorporating performance, spectator interaction, and nontraditional materials; many artists pursued new modes for painting and challenged distinctions between painting and sculpture. Including contemporary acquisitions in the DMA’s history along with new acquisitions, promised gifts, important local loans, and works in the collection being exhibited at the Museum for the very first time, Slip Zone reflects on the role institutions play in shaping and reconfiguring historical narratives.

Slip Zone is co-curated by Dr. Anna Katherine Brodbeck, Hoffman Family Senior Curator of Contemporary Art; Dr. Vivian Li, The Lupe Murchison Curator of Contemporary Art; and Vivian Crockett, former Nancy and Tim Hanley Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art. The exhibition is on view until July 10, 2022, and is included in free general admission.

“Slip Zone exemplifies the globally inclusive reconsideration of the art historical canon we work to present. This ambitious exhibition showcases the kinds of international dialogues we can reveal through our collection,” said Dr. Agustín Arteaga, the DMA’s Eugene McDermott Director. “In placing iconic artists in direct dialogue with their equally innovative but underrecognized contemporaries, and bringing the daring visions of all to the forefront, we tell a more honest and more dynamic story of a radical era in the evolution of art.”

Grounded in the strengths of the DMA’s collection, Slip Zone is organized in groupings of works that cover influential postwar movements in East Asia, Latin America, and the United States.

The exhibition features 72 artists. These include artists from the experimental collective the Gutai Art Association; artists who belonged to the Mono-ha and Tansaekhwa movements working with nontraditional materials; artists, mainly working in the United States, who pushed the optical and spatial effects of painting and sculpture; and artists from Latin America who participated in modern muralism as well as gestural and geometric abstract painting. Throughout the exhibition, pairings of works created by artists based in different geographic regions illuminate both formal and personal connections.

The members of the Osaka-based Gutai Art Association collectively pursued experiments in originality, forgoing an emphasis on individual authorship and allowing new perspectives to unfold. The Gutai’s early works frequently centered on their creative processes and performances, often exhibiting a liberating sense of playfulness.

Many of the Gutai’s performances and ephemeral works were captured by photographer Kiyoji Otsuji. Most of the Gutai’s works featured in Slip Zone did not involve the use of a paintbrush or even an easel, such as Shozo Shimamoto’s Bottle Crash painting (created by throwing glass bottles filled with paint and rocks onto canvas on the floor) and Kazuo Shiraga’s Kagayakeru-iro (Shining Colors) (painted by the artist using his feet). American artists like Sam Francis, Senga Nengudi, and Robert Rauschenberg were familiar with the works of the Gutai. Francis first traveled to Japan in 1957, when he visited the Gutai artist collective with PFrench critic Michel Tapié. The prominence of negative space in his works created soon after, like Emblem, alludes to the Japanese concept of ma (間), or the space in-between. This concept also appears in the work of painter Virginia Jaramillo. The influence of Sadamasa Motonaga and his 1956 installation Work (Water) can be felt in Nengudi’s Water Composition I.

Several postwar artists in East Asia—familiar with ink as well as oil painting—sought to create new types of abstraction drawn from both traditions. The immediacy of paper and ink informed a starkly literal and deliberate approach to materials. These tendencies appeared in several artists’ works during the late 1960s and 1970s, particularly those of the influential Mono-ha sculptural installation artists in Japan and the Tansaekhwa monochrome painters in Korea. Weight, tactility, and raw colors and materials predominated, such as the heaviness of the stone in Lee Ufan’s Relatum and the intricate wrinkles of paper pulp that draw the surface of Chung Chang-Sup’s “paintings.” The compulsive repetition and dense graphic symbols of ink calligraphy can be found in the work of Zao Wou-Ki and Mira Schendel.

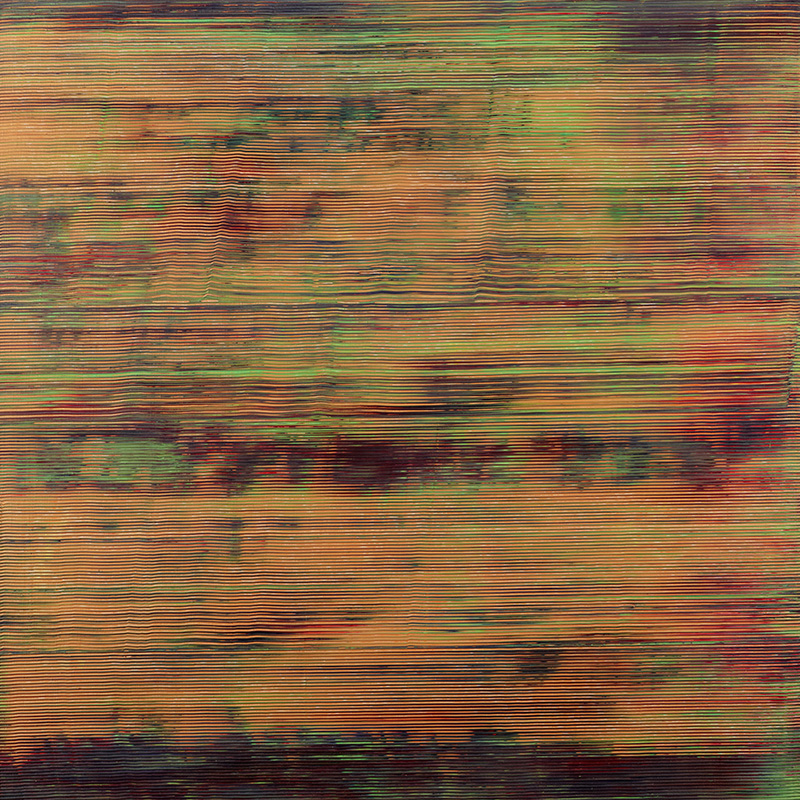

In the U.S., many artists pushed the optical and spatial effects of painting and sculpture through experimentation with new tools—such as Ed Clark’s use of push brooms, Jack Whitten’s use of saws, and Judy Chicago’s use of spray paint—and techniques adapted from traditional and industrial labor. Fred Eversley’s concave sculptures were informed by his career in engineering. Labor historically associated with women played a crucial role in the stylistic innovations of Alan Shields, Al Loving, and Sam Gilliam. In the 1960s and 1970s, debates about the political potentials and limitations of abstraction were central to the fight to include the work of Black artists in arts institutions. Even in attempts at inclusion, women artists were routinely excluded, and some addressed these questions directly in their work. Lynda Benglis’s Odalisque (Hey, Hey Frankenthaler) affirms Helen Frankenthaler’s importance to the genesis of the Color Field movement and nods to the artist’s method of pouring paint onto unprimed canvas, an example of which, Frankenthaler’s Myth, is exhibited nearby.

Through a diverse range of strategies, artists from Latin America played a critical role in the postwar period regionally and internationally. Mexican artists, primarily known for monumental murals, were particularly important in the U.S. as well as beyond the Americas. Jackson Pollock’s Figure Kneeling Before Arch with Skulls bears clear inspiration from José Clemente Orozco, and the American painter is exhibited in Slip Zone alongside his one-time instructor David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Artists in Brazil, Argentina, and Venezuela were interested in abstraction devoid of nationalist symbols for its potential as a universal language. José Antonio Fernández-Muro’s Violet Red on Gray showcases the use of geometric abstraction. Such compositions were inspired by mathematical functions, an approach championed by the Swiss Concretist Max Bill, who exhibited often in South America.

Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape were part of a short-lived movement in Brazil called Neoconcretism, which departed from the use of a mathematically based composition favored by Concrete artists. Their works included organic metaphors, and eventually viewers would be invited to participate in or manipulate certain works, like Clark’s Bicho—em si. Their works exemplify the wide-ranging potential of geometry.

“Slip Zone uniquely looks at connections between the Americas and East Asia—two regions that are not often thought of together—and reanimates the shared experimental spirit and potential of abstraction in this international postwar moment,” said the co-curators. “The remarkable artists in this show were unsatisfied with the notions of art they inherited and sought new materials and processes with like- minded artists, and not necessarily just in their home country. These influential artists were risk takers, shaping their own path.”