Shortchanged of History

I know this as fact: My roots, as far as my family’s time in North America, are steeped in the belief that White people are superior to other races.

It is only that belief, I know, that would allow anyone to feel it is OK to own another human, to see someone as a piece of property, an investment like a plow or a wagon.

In a fit of insomnia induced by a wicked bout of bronchitis, I began poking around my family’s genealogy a few years ago. My family history was a loosely gathered bit of lore strung together by intergenerational games of Telephone, so I was curious to see if the talk of leaving Ireland during the Potato Famine were legend or true, or if it was just a tale from a grandmother whose family was more interested in staying alive than documenting the past.

What I discovered instead is that I come from the closest thing to American royalty as you can get – a direct descendant of William Randolph who, with his wife Mary, are so connected to the important families of Virginia and the rest of colonial America that they’re known as the “Adam and Eve of Virginia.”

From them, we get connections to a veritable who’s who of history books — John Marshall, Pocahontas, Blands, Byrds, Carters, Beverleys, Fitzhughs, and Harrisons.

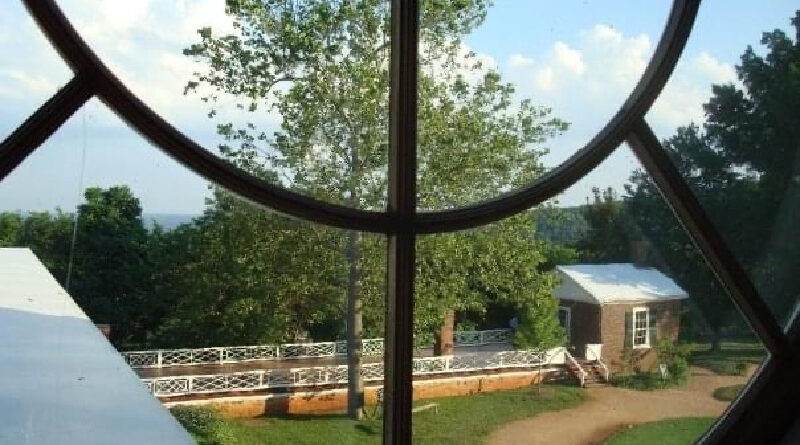

And yes, Thomas Jefferson, who married Martha Wayles Skelton, half-sister of the enslaved Sally Hemings.

As I clicked the little leaves on the genealogy platform that lead me like breadcrumbs to William Randolph, I met great-great-grandparents that served in the Confederate Army. As any child whose family grew up in the South, I expected it.

But reading about my Colonial kin, I found a family that not only was rich in history, but rich in actual money. Randolph amassed land — and lots of it — and often for what he imported to Virginia, like the 7,000 acres he received after he imported 72 indentured servants and 69 enslaved Black people to the colony of Virginia.

As their family grew, and those children forged their own paths, the Randolph family would become one of the largest land and slaveholders in Virginia, gaining much of their money from land, credit, and slave labor.

So with this backdrop, I sat and watched the debate over House Bill 3979, where much was made over the feelings and discomfort of White people forced to sit a little longer than they might like with the idea that there is more than one story about the making of America, and not everyone’s story is as shiny and cinematic as we’d like to pretend.

(Read:Our continuing coverage of the Texas legislature’s 87th session)

I hear it a lot, this premise that discussions about race are centered on the idea that the end result is the desire to make White people feel guilt for the actions of people long ago, to feel bad because of our skin color.

But what if I told you the real end goal isn’t that but is a desire that everyone acknowledge that being White does afford you some measure of safety, some measure of dignity, that Black Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Asian Americans are not automatically blessed with because our country historically has denied them of it?

We, as white people have had it throughout history, as if it’s almost our hereditary birthright as Americans to walk blithely down the street without worry, without the lady crossing paths with you pulling her purse a little closer, without that man sitting in his idling car hitting the door locks as you pass by.

I think the biggest thing I see when I look at my complicated family tree is that these people owned people, and my blood ties them to all the attendant problematic history with people like Thomas Jefferson, for instance.

There is no such thing as a benevolent slave owner. Thomas Jefferson owned people. George Washington owned people. James Monroe owned people.

And if you think it’s OK to own people because of where they were born and their skin color, that makes you a White supremacist. And that means that, yes, that.

What that tells me is this — we have to embrace the messiest parts of our history, we have to teach it, and we have to talk about it. We have to talk about the fact that this country was founded by teenagers and young adults who made the laws at an age when most of us nowadays are just getting married and paying off our student loans.

We have to talk about the fact that they owned people. We have to talk about the fact that the White House was built by enslaved people and that many of the things and people we hold up for veneration in our history have very problematic portions of their lives.

We have to reckon with the hypocrisy in writing that “all men are created equal,” but knowing that your household was served by free labor from enslaved individuals you had no intentions of ever freeing in your lifetime.

We have to reckon with the hypocrisy in writing that “all men are created equal,” but knowing that your household was served by free labor from enslaved individuals you had no intentions of ever freeing in your lifetime.

It’s important to look at these things, to discuss them, to unpack them and reckon with them, because when we look at all of this we can realize that there are no angels in our history, and there are no angels in our present and future either.

That’s not a bleak thought, it’s a thought that gives us the fuel to continue to study, look for reliable tellers of our present day, and make informed decisions free of hero-worship – the very thing a civics class should be for.

We cannot look at our history and not discuss the mess and hypocrisy along with the wins. We can’t pretend it doesn’t exist, because this pretending has actually caused everyone concerned pain. It’s why learning about white privilege is confusing and hard. It’s why we spent time talking about a bill that wasn’t necessary – people are scared because we’ve never really reckoned truly with our history with clear eyes. We only really look at the good parts, and gloss over the uncomfortable parts as asides.

These discussions of our history should come with the ability for people to acknowledge and discuss that their family’s history of America looks quite different from mine.

I can look at my family tree and feel regret, but not guilt. I am not responsible for the acts of William Randolph. Any wealth from that part of my family is long diluted and gone, but I can acknowledge that his Whiteness kept him alive, well fed, and wealthy, with access to resources his enslaved workforce did not have. That gave his family an advantage, which eventually, centuries later, meant that I could sit in my living room listening to the Texas legislature meet.

I feel sorrow that they owned slaves, because I know they could’ve done differently – Ann Cary Randolph and her founding father (and anti-slavery advocate) husband Gouverneur Morris fought Virginia’s growing use of enslaved people, and other Randolphs did so as well.

But I do not feel that my desire to see history through the eyes of those who had very different experiences is some kind of redemption owed because of William Randolph. I am not his redemptive arc.

My desire is borne of empathy, curiosity, and a sense of justice. My story is my story, and theirs belongs to them, and rightly, we should unabashedly discuss the wrongness of the things they partook in, without equivocating that maybe they had their reasons, because none of those reasons are good. We should discuss the fact that the entire country — not just the South — benefitted from unpaid labor, and we should talk about the fact that quite a bit of our country was built – both physically and economically – on the backs of enslaved Black men and women who provided unpaid labor.

We should discuss the fact that the entire country — not just the South — benefitted from unpaid labor, and we should talk about the fact that quite a bit of our country was built – both physically and economically – on the backs of enslaved Black men and women who provided unpaid labor.

We are not a nation of White people. We’ve never been a nation of White people (but we have largely been a nation for White people). We are only part of the story, and we need to embrace that, we need to teach that, and we need to teach what that means.

And that’s going to mean some uncomfortable conversations.

I was in my 20s before I learned about Black Wall Street and the massacre that happened there. I was in my 30s before I learned about Fred Hampton. I was in my 30s before I learned about COINTELPRO. I was in my 30s, too, when I learned about the Black patriots that were whitewashed out of the history of our country’s beginning.

When we shortchange teachers and students of the ability to actually discuss these things, to engage and couple this with social and emotional learning, we are leaving vast and critical swaths of our nation’s history out. Educations are incomplete.

We have to be able to discuss and reassure that democracy is messy everywhere, and often in our country. People are hypocritical, and at the end of the day, some of the things that we feel are our country’s strengths are actually weaknesses without full, clear-eyed knowledge of where we’ve been.

How do you get a child to believe that they can go to college, that they can graduate high school, that they’ll beat intergenerational poverty, that they’ll be successful, if we can’t even give them unfettered conversations about their history and how our history impacted them? How do we change a trajectory we only acknowledge as a data point, and never as a historical one? How do we engage students if they never see themselves in their history books as participants, only labor?

If talking about this hurts your feelings and makes you uncomfortable, imagine knowing – and never being able to ignore because of your skin color – that your family came here on a slave ship, often being fed just enough to keep them alive, to a life of intergenerational enslavement where children could be sold away from parents, where women had no ability to refuse sexual advances from their enslavers, where whippings and beatings were doled out.

Imagine how uncomfortable it feels to see statues and celebrations for people who fought for the right to keep owning your family members.

Imagine how uncomfortable it feels to watch a legislature pass permitless carry, knowing that a Black man carrying a gun is always seen as a threat by a group of people who would applaud a White man for exercising his second amendment rights.

When we create a bill that hamstrings discussions and learning about history, and then pass it in the middle of the night after ignoring the state constitution, we must reflect on who we’re actually protecting.

When we create a bill that hamstrings discussions and learning about history, and then pass it in the middle of the night after ignoring the state constitution, we must reflect on who we’re actually protecting.

I can tell you that right now, without my help, my fourth-grader can tell you what is going on in the world because he watches the news. He has access (with supervision) to the internet. He has friends. Your child does, too.

The genie is out of the bottle, the cat’s out of the bag.

We’re not protecting children with these bills, we’re protecting adults. We’re protecting adults from children, because adults are afraid of looking hypocritical, of being caught flat-footed when their child questions some view on race they’ve voiced at the dinner table.

In reality, our children are stronger and more resilient than we give them credit for. They’re more empathetic than we could ever dream of. They’re more inquisitive than we have the ability to address sometimes.

And the only thing that can stand in the way of the growth of any of those traits are adults.

I’m not going to stand in the way – and neither should anyone else, especially a bunch of legislators in the dead of night.

Bethany……THANK YOU, THANK YOU, THANK YOU for saying what needed to be said. Children are not benefited by having history withheld from them. We are quickly becoming a society of “giving everyone a trophy”. Where everything is happy and good……that is not reality and is definitely not life. In order to do better we must learn what has been done wrong. Winston Churchill said it best….”I am always ready to learn, although I do not always like being taught”. In order to move forward successfully we have to know history. PERIOD. There is no way around that. A lot of kids are going to know and learn things whether a law is passed or their parents don’t want them to know. They are hurting their kids but now allowing them to learn and know history.