A Deeper Dive Into COVID Learning Loss

Learning during a pandemic – with mass shutdowns of schools and inequities to access to everything from instructional supports to broadband internet – is uncharted territory. After all, the last major pandemic was in 1918, before compulsory high school, but just as public school became more popular.

And in 1918, some major metro public school systems stayed open, reasoning that schools were more able to provide sanitary conditions that would keep students safe – safer than if they were at home, where hygiene might be more hit or miss. Students with symptoms were quickly isolated, and sent to the hospital if necessary.

And learning looked vastly different in 1918, too, it’s safe to say. And it’s doubtful that the kind of granular, standardized data that schools generate now would tell us how much learning was impacted.

In short, it’s impossible to compare the two and come away with a definitive “this response is better than that one.” The expectations for students and schools are different.

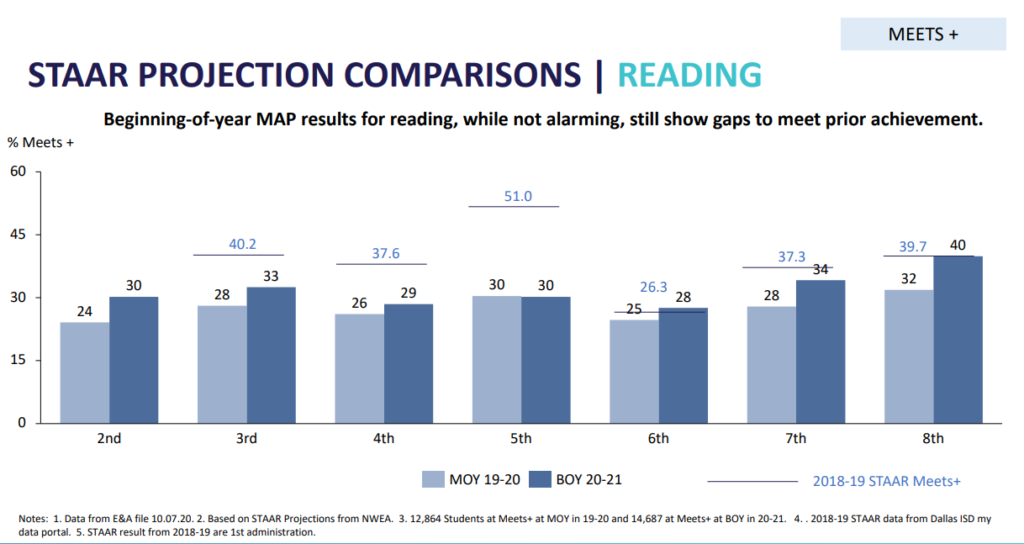

Last month, the Dallas ISD board of trustees learned just how much a hastily assembled curriculum in the Spring, followed by a summer still hard-hit by COVID-19, and a fall that offered both in-person and distance learning would impact learning, thanks to data from a district-wide assessment called the Measure of Academic Progress, or MAP.

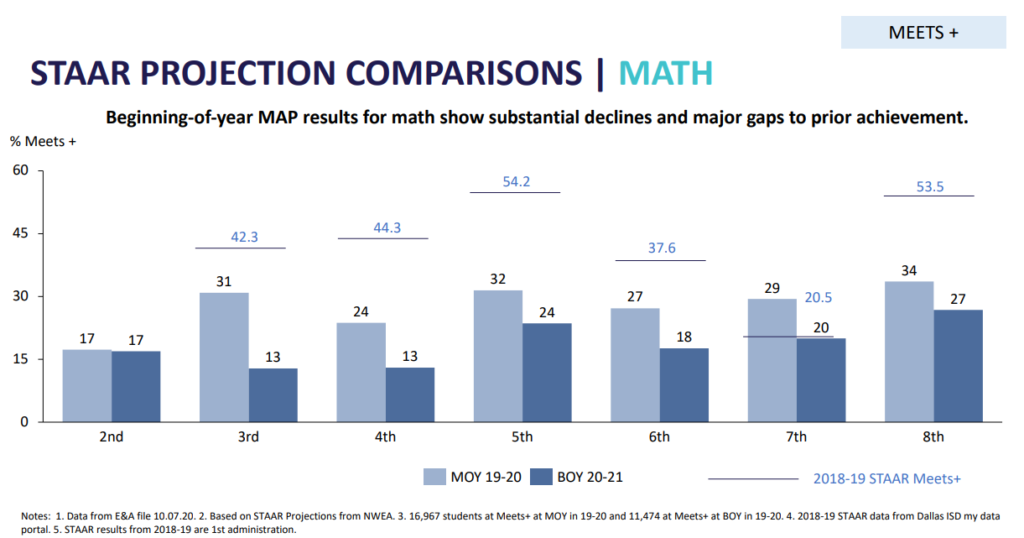

Dallas ISD’s MAP scores were troubling, but also a little unexpected. There were losses, for sure, but largely in math.

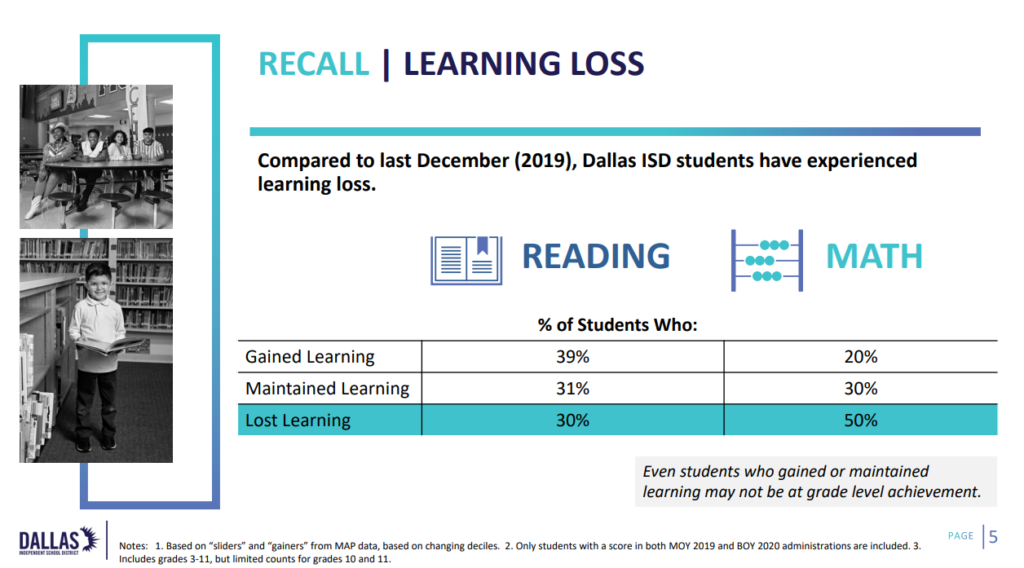

Almost a third of all students experienced reading loss, and half of all students lost vital math skills, MAP scores from the beginning of the school year revealed. Nearly every elementary and middle school student in the district came to school in September with fewer math skills than kids the year before in the same grades.

But that made us wonder – districts across the country use some form of assessment to measure year-over-year progress, as well as mid-year and end-of-the-year progress. Several use MAP. How did Dallas ISD compare?

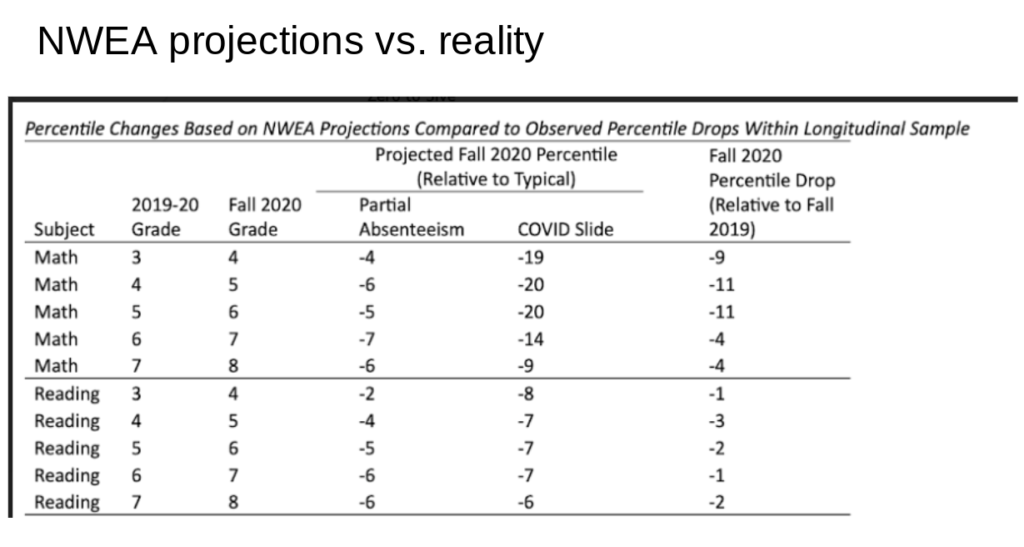

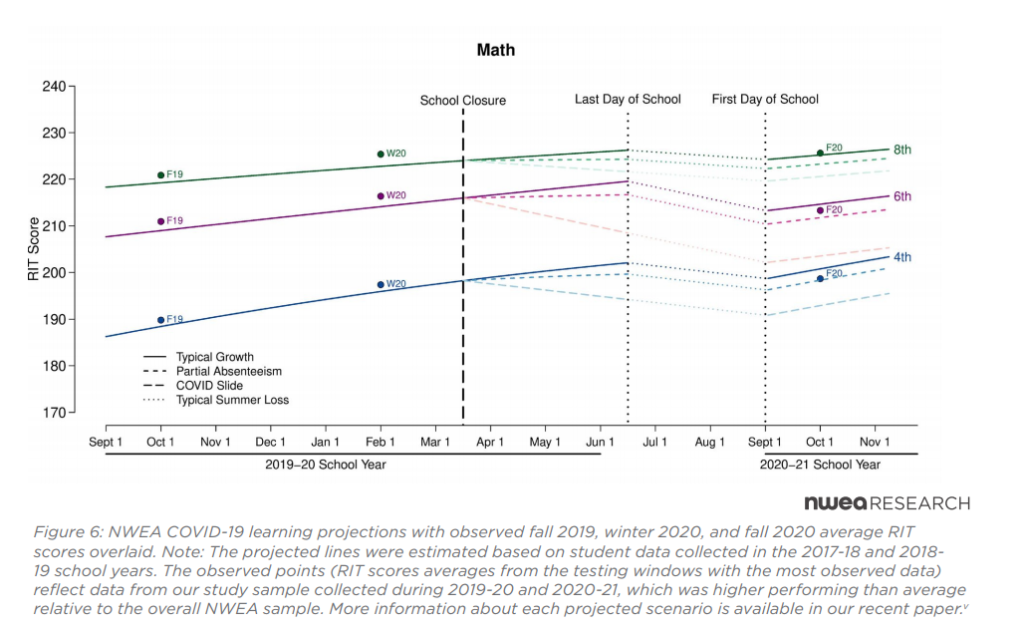

I got my first look at answers last week, thanks to a sneak peek at a report from researchers at NWEA, who created the MAP assessment.

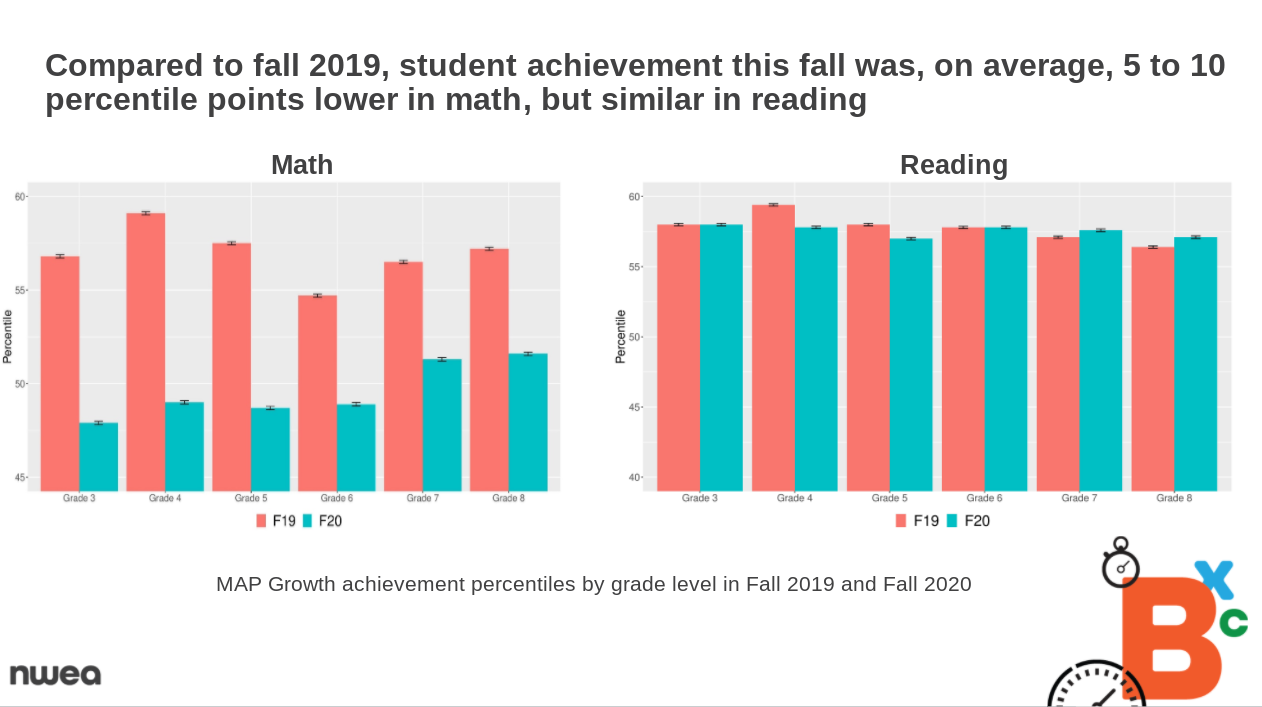

The report took a look at how roughly 4.4 million students in grades 3-8 scored in fall 2019 compared to students in the same grades in fall 2020. Researchers also explained last week in a webinar how MAP assessment data compared to projections from other organizations, including Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes and McKinsey, as well as reports from Renaissance and Curriculum Associates’ iReady data.

Not quite 40% of Dallas ISD students made gains in reading compared to the beginning of 2019, while 31% maintained their reading level, and 30% lost learning. In math, only 20% gained, while 30% maintained, and 50% lost learning.

NWEA initially projected massive losses in math and reading – but instead, they saw what Dallas ISD saw – troubling drops in math, but relatively small dips in reading, with the average student losing five to 10 percentage points in math and very little in reading.

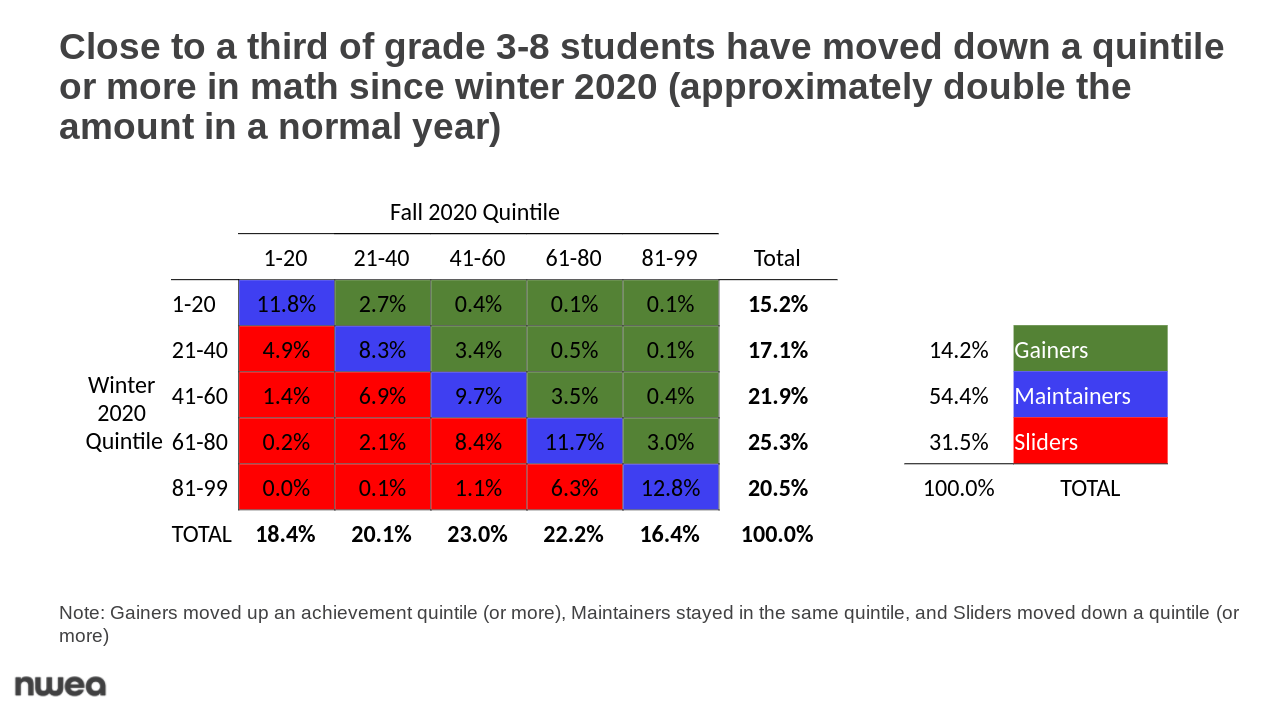

For math, 14.2% fell into the gain category for math, 54.4% maintained, and 31.5% lost math knowledge.

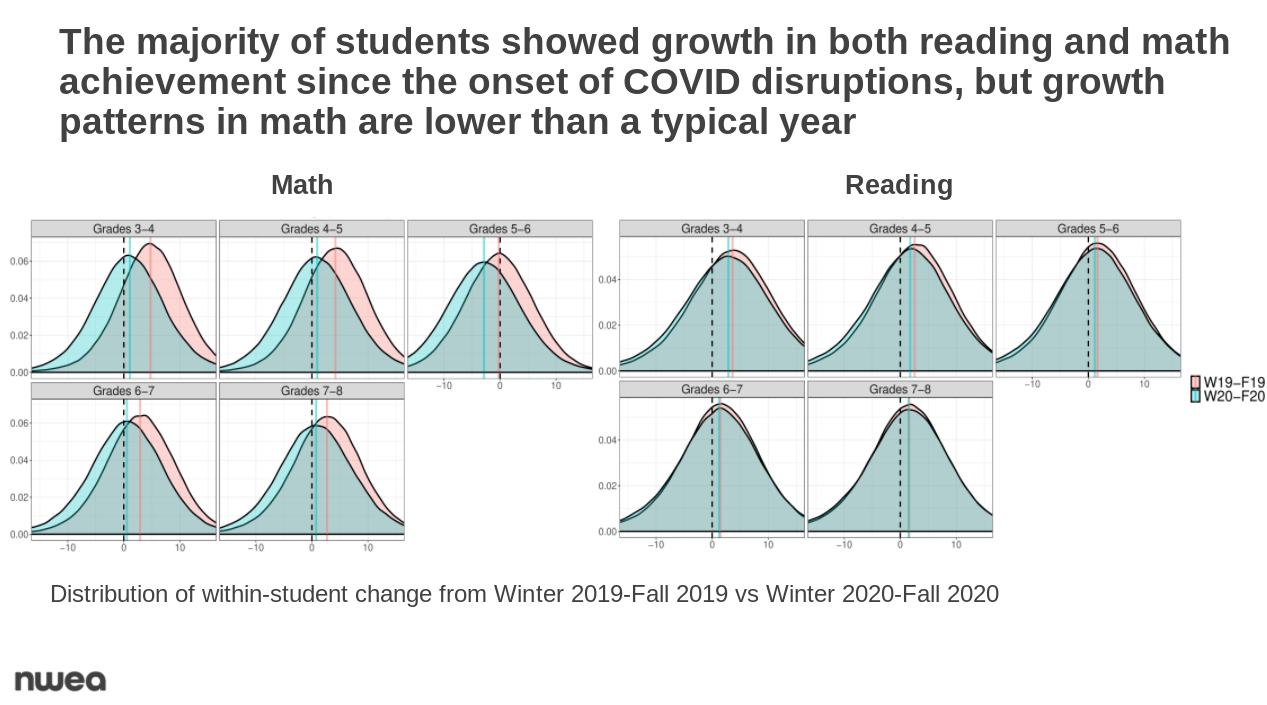

“Focusing on within-student growth from winter 2020 to fall 2020, we saw that on average, students showed growth in both math and reading across grade levels, except for math in grades 5 and 6,” researchers explained. “In almost all grades, most students made some learning gains in both reading and math since the COVID-19 pandemic started, though gains were smaller in math in 2020 relative to the gains students in the same grades made in the winter 2019-fall 2019 period.”

The crux, the researchers said, was not that this was necessarily a loss of skills, but a phenomenon they called “unfinished learning” – that is, the abrupt end to traditional schooling in the spring meant that students didn’t have the time and resources to complete the process of picking up additional math and reading skills.

Researchers were quick to reiterate – the estimates they’re seeing now as they begin to analyze the data gleaned from fall MAP assessments may underestimate the losses, but early projections of massive losses may be overestimates.

Most students did make learning gains in both math and reading during the spring and summer. But gains were smaller than normal in math, and the sample size was smaller because fewer students returned and took the test this year – and there were more students taking the test at home, versus the controlled school environment.

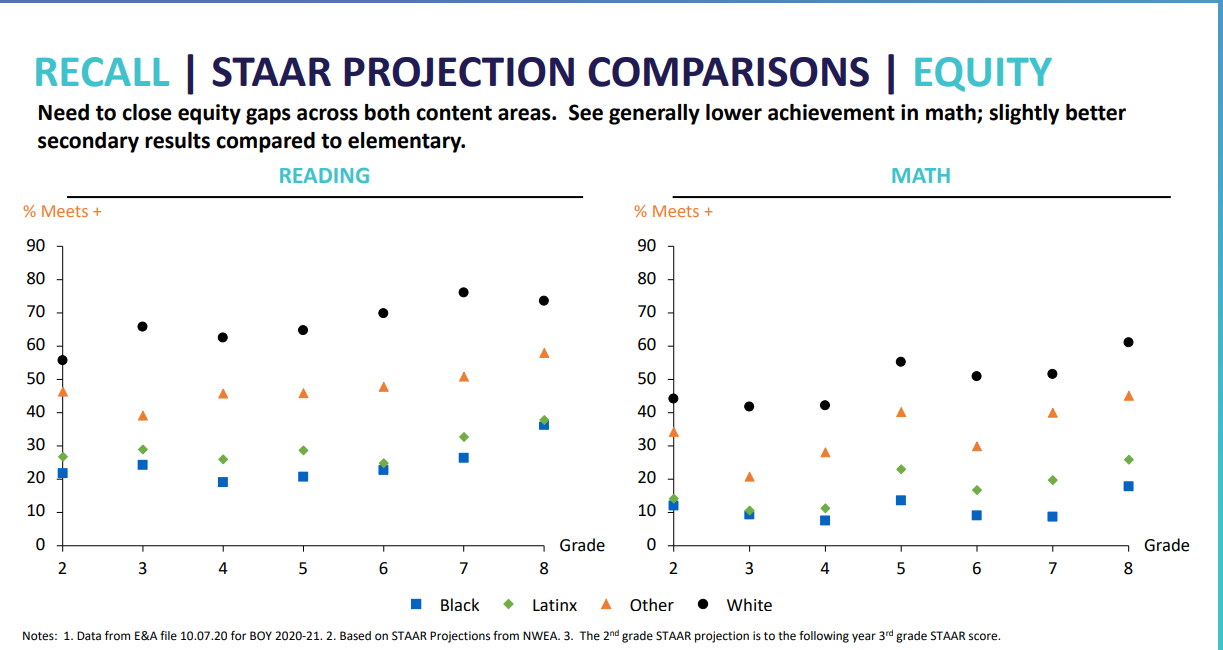

“The most concerning scenario is that students not testing in fall 2020 are disproportionately from disadvantaged backgrounds,” the NWEA’s Angela Johnson and Megan Kuhfeld said. “Not accounting for these students would produce underestimated learning loss and achievement gaps, potentially resulting in under-provision of support and services to the neediest students.”

The two said that a look at subjects and grades found a pattern: A larger fraction of attriters (students who disappeared from the sample size between last fall and this fall) were ethnic/racial minority students, students with lower achievement levels last fall, and students in schools with higher concentrations of socioeconomically-disadvantaged students.

“The findings from our attrition analyses suggest that considerable caution is warranted when interpreting fall 2020 assessment results,” the two said. “ … a sizable population of the most vulnerable students were not assessed in fall 2020, and their achievement is not reflected in the data as a result. These systematic differences between attriters and students who tested mean that the impacts of COVID-19 on student achievement are likely underestimated.”

The NWEA report said that students may have opted out of testing because they lacked reliable computers and internet access, or because they have left school altogether.

“Either scenario presents an urgent call for intervention,” the report said.