Sheltered Diaries: Talking as a Family About Race

How do we talk about race – and what happened to George Floyd – as a family? What are age-appropriate ways to discuss race and other social justice issues with children?

I’ve been asked that a lot over the past week or so, and I need to be honest: While we’ve talked in vague terms about inequality, I don’t think we’ve ever had a lot of targeted discussions about race as a family. My husband and I have had discussions, for sure. But with Tiny – those conversations, in retrospect, were often more vague, more piecemeal, despite my good intentions.

I felt, as friend after friend asked how to talk to their elementary schooler about race, that maybe we hadn’t done enough. And perhaps you wonder if you have, too. After all, like so many topics, gauging what your child is ready to hear can be a bit of a tightrope.

But this week, I found myself right smack in the middle of a conversation with Tiny. Now, as I’ve said before, I’ve never really hidden what I do – even when I cover something tough – from Tiny. I might give age-appropriate explanations, but he knows what I cover and write about.

The other day, he was looking over my shoulder as I edited some things.

“Why does that say ‘Mama, mama?'” he asked.

I had to stop for a second and formulate a response. I don’t know if I was especially eloquent, and it was at the end of the day so he wasn’t super invested in listening hard, but he did surprise me by wanting to talk about what I told him.

“A man named George Floyd died because the police killed him. A policeman put his knee on his neck hard, and he couldn’t breathe.”

Tiny’s eyes got big.

“While he was asking them to stop, he asked for his mama, just like you would if someone was hurting you.”

He sat for a second, and said, “Why wouldn’t they get up?”

Now, what followed was a discussion about race, and the police, and a 90-second explanation on slavery that obviously will have to be revisited because it was bedtime.

But what struck me later, as I started writing my pieces for the next day, was what he asked. Not, “what did he do?” or “Why was in he trouble?”

“Why wouldn’t they get up?” he asked.

I don’t know that I’ve ever felt more inadequate as a parent or as someone who works with words until that moment, because the answer to that question is a lot to unpack.

But if you’re like me, and your children are like Tiny, that response will likely also need some kind of plan of action. Tiny is a doer – and he’s already asking what he should do, what we can do.

So over the next few weeks, I hope to provide you with what I’ve found – and if you have resources you’d like to share with readers, please reach out. This week, I had a conversation with Mary Pat Higgins, Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum president and CEO.

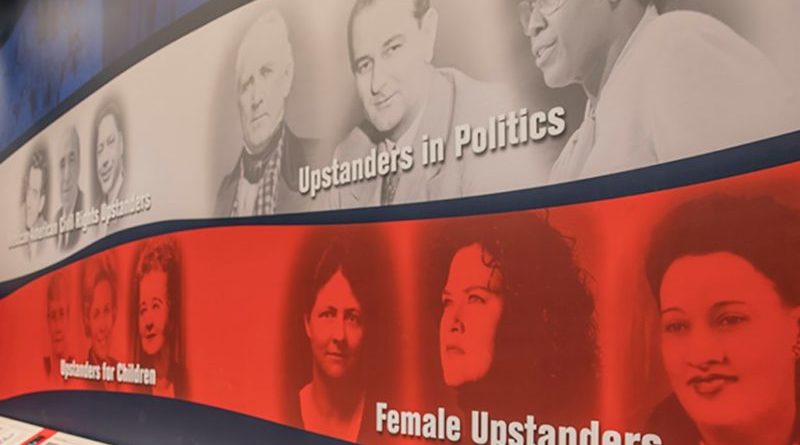

Last year, when the museum opened, museum officials said their ultimate goal is to teach 100,000 student visitors annually how to be up-standers – people who stand up against injustice to ensure human rights are upheld.

Last year, when the museum opened, museum officials said their ultimate goal is to teach 100,000 student visitors annually how to be up-standers – people who stand up against injustice to ensure human rights are upheld.

If the museum wasn’t shuttered due to COVID-19, you’d be able to visit the Pivot to America Wing, which takes visitors through American history and the country’s civil rights struggles, and includes a replica of the Piccadilly Cafeteria in Dallas, where protesters gathered for four weeks after a black man named Clarence Broadnax was refused service there in 1964.

But even though the museum is dark right now, there are still a vast array of resources for families to access. Those resources include a virtual experience the museum crafted by pairing with Matterport, a service often used by real estate agents to show off listings, to give a “walk-through” visit experience to one of its exhibits – The Fight for Civil Rights in the South.

The exhibit, which debuted in February and has been extended through Jan. 14, 2021, combines two photography exhibitions covering the African American struggle for civil rights and social equality in the 1960s – “Selma to Montgomery: Photographs by Spider Martin” and “Courage Under Fire: The 1961 Burning of the Freedom Riders Bus.”

PN: The museum has made a civil rights exhibit available virtually since the pandemic closed museums. How important was it to you to make that available – and how can parents and families use this as a way to talk about race?

Higgins: “We thought it was very important to give people virtual access to this amazing exhibition, The Fight for Civil Rights in the South. This exhibition combines two prestigious photography exhibits covering two significant steps in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s -the 1961 Burning of the Freedom Riders Bus in Anniston, AL, and the March from Selma to Montgomery in 1965.

Photographer Joseph Postiglione brought national attention to the violent resistance to desegregation through his photos of the Freedom Riders, engaging in peaceful protest against segregation on public transportation. On May 14, 1961, riders nearly died when their bus was fire-bombed by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Photographer James ‘Spider’ Martin captured the iconic marches to Montgomery, including images of Dr. Martin King, Jr. leading more than 2,000 marchers across the Edwin Pettus Bridge, documenting this nonviolent action that helped lead to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Studying this history reminds us that the journey for civil rights has spanned many decades and helps us understand the roots and legacy of racism in our country.

We have created a worksheet that encourages students to reflect on the exhibit and history displayed in it. It is important to know this history before opening the conversation with children, so parents should try to brush up on their American history.

While we have made great strides, thanks to the efforts of incredible Upstanders who peacefully protested for change, there is still much work to do to eliminate systemic racism and ensure equity and justice for African Americans. The Upstanders of today must continue the work of fighting for civil rights for all our citizens.”

PN: We hear the term upstander – what is that?

Higgins: “We define an Upstander as a person who stands up for other people and their rights; combats injustice, inequality, or unfairness; and sees something wrong and works to make it right.

Being an Upstander is something to which we can all aspire. It is something we teach at the museum through the examples of historical figures who embraced this behavior.”

PN: How do we talk to our children about being an upstander? What are some age-appropriate ways to do that?

Higgins: “We have some wonderful, age-appropriate resources for students on our website: www.dhhrm.org in the Educator – Online Resources tab. You can find a terrific video explaining what it means to be an Upstander that gives some examples of real-life Upstanders.

You can start by encouraging your children to stand up for their peers when they see that they aren’t being treated fairly or kindly. For instance, if they see a classmate sitting by themselves in the lunchroom, they could sit with them and try to get to know them. If they see a peer being bullied, in person or online, they can step up to say it isn’t right.”

PN: Race – and social justice – is an uncomfortable subject for many adults to discuss – and many parents we’ve talked to say they feel like they’re at a loss for answers to their children’s potential questions if they did initiate discussions about it. Do we need all the answers before having these talks, or is there a case for just admitting that we don’t have all the answers?

“I think it’s important for our children to know that we don’t have all the answers, but that it is important to try to understand how other people feel and why they feel that way. It’s never too early to start teaching your children about the importance of empathy and listening.”

Higgins: “I think it’s important for our children to know that we don’t have all the answers, but that it is important to try to understand how other people feel and why they feel that way. It’s never too early to start teaching your children about the importance of empathy and listening. Then, you can learn more about these issues together. One great way to do this, is by participating in some of our virtual summer camps together. For children ages 6-10 we have Camp Upstander, and for students ages 11-18 we have the Upstander Institute. There is a different focus each week, ranging from Understanding Bias and Empowering Leadership, to learning about the Holocaust and other genocides for older students, and spreading kindness and embracing difference for younger students.”

PN: How early do we talk about social justice with our children?

PN: How early do we talk about social justice with our children?

Higgins: “You can’t start too early, but you need to do it an age-appropriate way. For instance, you can read books like The Sneetches by Dr. Seuss to young children and talk through the fact that difference is good, natural, and is something with which we should become comfortable.

Parents can participate with their young children in Camp Upstander, where they will tackle themes such as embracing differences and building respect with fun, engaging activities.

Teaching Upstander behavior is applicable at any age. Children watch their parents closely, so modeling Upstander behavior is crucial for them to see in their parents from their youngest days.”

Pingback:Sheltered Diaries: Good Choices Have a Ripple Effect | People Newspapers