Telling the Story of Reagan’s Shooter

When John Hinckley Jr. shot President Ronald Reagan in the chest on March 30, 1981, his school friend Kirk Dooley was driving down to Austin for a business meeting. He almost had a wreck when the news came in over the radio. “It was shocking,” Dooley said. “You couldn’t put two and two together.”

When John Hinckley Jr. shot President Ronald Reagan in the chest on March 30, 1981, his school friend Kirk Dooley was driving down to Austin for a business meeting. He almost had a wreck when the news came in over the radio. “It was shocking,” Dooley said. “You couldn’t put two and two together.”

By the time Dooley got to Austin and sat down in his meeting, “a guy sits down next to me and says, ‘Are you Kirk Dooley? I’m from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram: can you tell me about John Hinckley.”

This was not the last time Dooley would be asked to tell the story of Reagan’s shooter.

Hinckley was released Sept. 10 from the psychiatric hospital where he has lived under close surveillance since courts found him not guilty by reason of insanity 35 years ago. Under terms of his release, he will live with his mother in Virginia with restricted access to media and a tracking device when he leaves the house.

After Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated John F. Kennedy in 1963, cult followings sprang up around a multitude of conspiracy theories. Oswald was a Russian spy. A communist. A patsy. He was working for the CIA, the KGB, the Mafia, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. Aliens.

Hinckley was different. As he later testified in court, he shot Reagan to impress Jodie Foster, with whom he had become obsessed after watching the movie Taxi Driver.

But this answer, at once so far-fetched and so simple, was not satisfactory. Media descended on Hinckley’s hometown, trying to dig through his past and find an explanation, to understand what led a kid from Highland Park to a McDonald’s in Washington D.C. where he decided to go out, load his gun, and assassinate the president.

The stories that ran in the following months painted a picture of an increasingly abnormal youth. The Dallas Morning News ran headlines like, “Hinckley’s hidden side emerges,” “John Hinckley’s long, dark journey,” and “Hinckley never measured up to pressure.”

“The guy they were describing and the guy I knew didn’t match up,” Dooley said. “He was a normal guy. People liked him.”

Hinckley was the president of their seventh-grade class in junior high. In high school, when Dooley was captain of the basketball team, Hinckley was the manager, and they got along well.

“He was sort of quiet,” Dooley said, “but that’s not unusual.”

A few nights after the shooting, their close friends got together. “There was a lot of media pressure,” Dooley said. “For people who weren’t used to being interviewed, it was really intimidating. They were stressed out about how many people were showing up at their house, calling them. We all had the same thing to say – that he was normal.”

Dooley was in the media at the time. “My friend said, we don’t like being interviewed. … Would you do the talking for us? So I spoke for the class,” Dooley said. “I did a lot of interviews.”

He did 66. Dooley said he took on this mantle out of journalist’s responsibility: he didn’t think the right story was being told.

In the national consciousness, Hinckley was the specter of the junior high golden boy gone wrong.

But to Dooley, Hinckley’s mental illness was something that “could happen to anybody.” It was something “that happened after.”

“Don’t blame Dallas, don’t blame the high school,” Dooley said. “I don’t think our collective experience was a part of what happened.”

Dooley was fiercely protective of his friends, and of their shared past.

“The one thing that still kind of leaves a bad taste in my mouth is how John’s family suffered for what he did,” he said. “The parents, and his brother and sister. To be related to a presidential assassin changes your life.”

But there’s no bitterness when he talks about Hinckley. “All these years I’ve just been hoping that he can get through the mental illness,” he says. “I think there will be a time when I can help reconnect his past.”

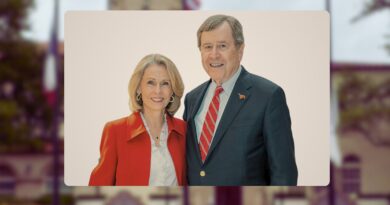

Dooley, who also founded Park Cities People, wrote for the Dallas Morning News, and has authored six books, is now involved with a Metrocare Services clinic that provides free mental health services to veterans.

“In a way it’s odd being friend of an assassin,” Dooley says. “But, he’s a friend, and I think there’s a side to the story that needs to be told. And that’s that he grew up normal. When I knew him, there was no sign.”